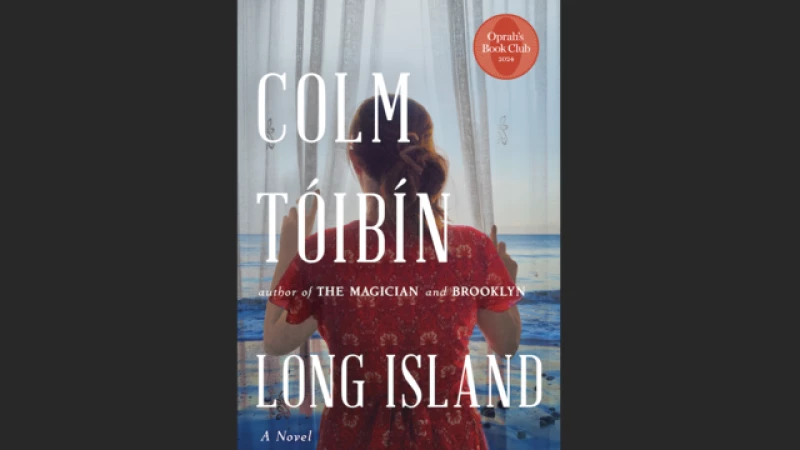

Oprah Winfrey has chosen "Long Island" by Colm Tóibín as her latest book club selection.

Published by Simon & Schuster, "Long Island" serves as the sequel to Tóibín's previous bestseller "Brooklyn" from 2009. The story follows Eilis Lacey, a young woman who departed her small Irish hometown in pursuit of a new life in America.

In "Long Island," the narrative progresses over two decades later, depicting Eilis as a wife to a plumber named Tony and a mother to two teenagers.

Take a glimpse at an excerpt below.

"That Irishman has been here again," Francesca mentioned, taking a seat at the kitchen table. "He has visited every house, but his search is for you. I informed him that you would be back soon."

"What is his purpose?" Eilis inquired.

"I tried everything to extract it from him, but he remained silent. He specifically asked for you by name."

"He is aware of my name?"

Francesca's grin carried a hint of mischief. Eilis admired her mother-in-law's sharpness, along with her clever sense of humor.

"Another man is the last thing I require," Eilis remarked. "Who are you referring to?" Francesca retorted.

Francesca and Eilis shared a laugh before Francesca stood up to leave. Eilis watched from the window as Francesca carefully made her way across the damp grass to her own house.

Soon, Larry would return from school, followed by Rosella from after-school study, and then Tony would arrive after parking his car outside. Eilis always finished work at three so she could be there when her family came home each day. It was a moment she cherished and didn't want to miss. She thought about having a cigarette, but after finding Larry smoking, she had struck a deal with him to quit completely if he promised not to smoke again. Despite this, she still had a packet of cigarettes upstairs.

When the doorbell rang, Eilis got up lazily, assuming it was one of Larry's cousins coming to call him out to play. However, as she approached the door, she noticed the silhouette of a grown man through the frosted glass. It wasn't until he called out her name that she realized this was the man Francesca had mentioned. She opened the door.

"You are Eilis Fiorello?"

The man's accent was Irish, with a hint of Donegal, reminiscent of a teacher she once had. His stance, as if ready to be challenged, brought back memories of home.

"I am," she replied.

"I have been searching for you."

His voice carried a hint of aggression. She pondered if Tony's dealings could be the reason.

"That seems to be the talk."

"You are the spouse of the plumber?"

Considering the question impolite, she chose not to respond. "He's quite skilled at his work, your husband. It appears he's in high demand."

The man paused, glancing over his shoulder to ensure privacy.

"He repaired everything in our home," he continued, pointing a finger at her. "He even went beyond the initial scope. In fact, he made repeat visits when he knew the lady of the house would be present and I would not. And his plumbing skills are so exceptional that she's expecting a baby in August."

He stood back and smiled broadly at her expression of disbelief. "That's right. That's why I'm here. And I can tell you for a fact that I am not the father. It had nothing to do with me. But I am married to the woman who is having this baby and if anyone thinks I am keeping an Italian plumber's brat in my house and have my own children believe that it came into the world as decently as they did, they can have another think."

He pointed a finger at her again.

"So as soon as this little bastard is born, I am transporting it here. And if you are not at home, then I will hand it to that other woman. And if there's no one at all in any of the houses you people own, I'll leave it right here on your doorstep."

He walked towards her and lowered his voice.

"And you can tell your husband from me that if I ever see his face anywhere near me, I'll come after him with an iron bar that I keep handy. Now, have I made myself clear?"

Eilis wanted to ask him what part of Ireland he was from as a way of ignoring what he had said, but he had already turned away. She tried to think of something else to say that might engage him. "Have I made myself clear?" he asked again as he reached his car.

When she did not reply, he made as though to approach the house once more.

"I'll be seeing you in August, or it could be late July and that's the last time I'll see you, Eilis."

"How do you know my name?" she asked.

"That husband of yours is a great talker. That's how I know your name. He told my wife all about you."

If he had been Italian or plain American, she would not have been sure how to judge whether he was making a threat he had no intention of carrying out. He was, she thought, a man who liked the sound of his own voice. But she recognized something in him, a stubbornness, perhaps even a sort of sincerity.

She had known men like this in Ireland. Should one of them discover that their wife had been unfaithful and was pregnant as a result, they would not have the baby in the house.

At home, however, no man would be able to take a newborn baby and deliver it to another household. He would be seen by someone. A priest or a doctor or a Guard would make him take the baby back. But here, in this quiet cul-de-sac, the man could leave a baby on her doorstep without anyone noticing him. He really could do that. And the way he spoke, the set of his jaw, the determination in his gaze, convinced her that he meant what he was saying.

Once he had driven away, she went back into the living room and sat down. She closed her eyes.

Somewhere, not far away, there was a woman pregnant with Tony's child. Eilis did not know why she presumed that the woman was Irish too. Perhaps her visitor would be more likely to order an Irishwoman around. Anyone else might stand up to him, or leave him. Suddenly, the image of this woman alone with a baby coming to look for support from Tony frightened her even more than the image of a baby being left on her doorstep. But then that second image too, when she let herself picture it in cold detail, made her feel sick. What if the baby was crying? Would she pick it up? If she did, what would she do then?

As she stood up and moved to another chair, the man, so recently in front of her, real and vivid and imposing, seemed like someone she had read about or seen on television. It simply wasn't possible that the house could be perfectly quiet one moment and then have this visitor arriving in the next.

If she told someone about it, then she might know how to feel, what she should do. In one flash, an image of her elder sister, Rose, dead now more than twenty years, came into her mind. All through her childhood, in even the smallest crisis, she could appeal to Rose, who would take control. She had never confided in her mother, who was, in any case, in Ireland with no telephone in her house. Her two sisters-in-law, Lena and Clara, were both from Italian families and close to each other but not to Eilis.

In the hallway, she looked at the telephone on its stand. If there was one number she could call, one friend to whom she could recount the scene that had just been enacted at her front door! It wasn't that the man, whatever his name was, would become more real if she described him to someone. She had no doubt that he was real. What she wanted was someone to offer an interpretation of what had happened that would give her some consolation. At the moment, she herself could see none.

She picked up the receiver as if she were about to dial a number. She listened to the dial tone. She put the receiver down and lifted it again. There must be some number she could call. She held the receiver to her ear as she realized that there was not.

Did Tony know this man was going to appear? She tried to think about his behavior over the previous weeks, but there was nothing out of the ordinary that she could think of. At the very least, he had come home some days having been with this woman, pretending that everything was normal. At the most, he also knew what the threat was, and he was aware that the man intended to visit Eilis and he did not warn her.

Eilis went upstairs, looking around her own bedroom as if she were a stranger in this house. She picked up Tony's pajamas from where he had left them on the floor that morning, wondering if she should exclude his clothes from the wash. And then she saw that that made no sense at all.

Maybe, instead, she should tell him to remove himself to his mother's house and she could talk to him when she had collected her thoughts.

But what, then, if it was a misunderstanding? She would be in the wrong, too ready to believe the worst of a man to whom she had been married for more than twenty years.

She went into Larry's room, examining the large-scale map of Naples that he had pinned to the wall. He had insisted that this was his real homeplace, ignoring her efforts to tell him that he was half Irish and that his father was actually born in America and that his grandparents, in any case, came from a village south of the city. "They sailed to America from Naples," Larry said. "Ask them."

"I sailed from Liverpool, but that does not mean I am from there." For a few weeks, as he worked on a class project about Naples, Larry became like his sister, fascinated by detail and ready to stay up late to finish what he had begun. But once it was completed, he had reverted to his old self.

Now, at sixteen, Larry was taller than Tony, with dark eyes and a much darker complexion than his father or his uncles. But he had inherited from them, she thought, a way of demanding that his interests be respected in the house while laughing at the pretensions to seriousness apparent in his mother and his sister.

"I want to come home," Tony often said, "get cleaned up, have a beer and put my feet up."

"And that is what I want too," Larry said.

"I often ask the Lord," Eilis said, "if there is anything else I can do to make my husband and son more comfortable."

"Less talk and more television," Larry said.

In the quiet cul-de-sac where Tony's brothers Enzo and Mauro resided with their families, a different dynamic existed among the children. While Rosella and Larry engaged in lively debates, the teenagers in the neighborhood did not speak as freely. Rosella thrived on presenting facts and uncovering flaws in arguments, while Larry preferred to inject humor into discussions. Eilis found herself siding with Rosella, just as Tony would chuckle at Larry's witty remarks before they were even fully delivered. "I'm just a plumber," Tony would jest. "My expertise lies in fixing leaks, not in politics. No plumber will ever reach the White House unless they have pipe problems."

"But the White House is notorious for leaks," Larry countered. "Ah, so you do have an interest in politics," Rosella teased. "If Larry applied himself," Eilis mused, "he might surprise us all."

Eilis sensed Rosella's arrival and wondered if their usual banter at the dinner table would resume. A part of her life felt like it had concluded with the recent visit from a certain man, whose decision regarding his wife's pregnancy had unforeseen implications for Eilis and Tony. Despite her wishes for a different outcome, she acknowledged the futility of trying to alter the course of events.

During their nightly meals, Tony regaled the group with tales of his workday, recounting the intricacies of his clients' homes and the common grime found near sinks and toilets. Eilis only intervened to halt his storytelling when Rosella and Larry were in fits of laughter.

"That is what puts the food on the table," Larry would say. "But wait, things were worse this afternoon," Tony would begin again.

In the future, Eilis thought, she would watch him to see what he was concealing.

Having shouted a greeting to Rosella, Eilis went back into the main bedroom and closed the door. She was trying to imagine Rosella's response, and Larry's, to the news that Tony had fathered a child with another woman. Larry, despite his swagger, was, she thought, innocent, and the idea that his father had had sex with a woman in whose house he was fixing a leak would be beyond him, whereas Rosella read novels and discussed the most lurid court cases with her uncle Frank, the youngest of Tony's brothers. If a husband choked his wife and then chopped her up, Frank, who was a lawyer, the only one among the brothers who had gone to college, would learn even more alarming details and share them with his niece. Finding out that her father had been involved with another woman might not shock Rosella, but Eilis could not be sure.

She sat on the edge of the bed. How would she even tell Tony that the man had called? For a second, she wished there was some- where she could go, a place where she would not have to contemplate what had happened.

The extra room they had built onto the house, once Eilis's office, was now used by Rosella and Larry for study, although Larry, in reality, spent little time there.

"I can make you tea, or even coffee, if you want," Eilis said when she found Rosella there.

"You did that yesterday," Rosella replied. "It's my turn."

Rosella had a way of composing herself, not smiling, remaining silent, that set her apart from her cousins. They used any excuse to burst into loud laughter or an expression of wonder while Rosella looked to her mother in the hope that she might soon be taken away from this family gathering to the calmness of their own house. When Tony and Larry set about disturbing this calmness, often by vying with each other in replicating the radio commentary on baseball games, Rosella retired to her study, as she called it. She even had Tony put a lock on the door to prevent Larry from barging in when she was trying to concentrate.

At times, Eilis found it stifling living beside Tony's parents and his two brothers and their families. They could almost see in through her windows. If she decided to go for a walk, one of her sisters-in-law or her mother-in-law would ask her where she had gone and why. They often blamed her interest in privacy and staying apart as something Irish.

But, since Rosella's looks were so Italian, they did not really think there was anything Irish about her. Thus, they could not imagine where her seriousness came from.

Rosella tried not to stand out. She paid attention to everything her aunts and cousins said and commented on new clothes and hairstyles, but she had no real interest in fashion. They would have thought her bookish and eccentric, Eilis knew, if she had not been so good-looking.

"All her grace and beauty," her grandmother said, "comes from my mother and my aunt. It passed over our generation—God knows I didn't get any of it—and then came to America. Rosella belongs to an earlier time. And those women on my side of the family had brains as well as beauty. My aunt Josefina was so clever that she almost didn't get married at all."

"Would that be clever?" Rosella asked.

"Well, sometimes it would, but not in the end, I think. And I am sure you will be snapped up when the time comes."

Two days a week, between school and supper, Rosella crossed from her own house to her grandmother's and they talked for an hour.

"But what do you talk about?" Eilis asked. "The reunification of Italy."

"Seriously."

"You know, of her three daughters-in-law, she likes you best." "No, she doesn't!"

"Today, she asked me to pray with her." "For what?"

"For Uncle Frank to find a nice wife." "She means an Italian wife?"

"She means any wife at all. And with his brains, she says, and his salary and bonuses, and the fact that he lives in Manhattan, he should have women following him in the street. I don't think she cares whether the woman is Italian or not. Look what Dad found when he went to an Irish dance."

"Would you not prefer to have an Italian mother? Would it not make life simpler?"

"I like things the way they are."

While flipping through the books on Rosella's desk, Eilis couldn't help but notice how much her life depended on the hard work and dedication of her father and his two brothers. Their reputation in the trade, built on trust and reliability, extended far beyond the boundaries of a town, creating a sense of intimacy within their community. However, it was only a matter of time before rumors about Tony's affair with a woman he met during work would start circulating, much like gossip in a small village.

Eilis had been successful in avoiding imagining Tony in his work attire inside the woman's house. But now, she couldn't shake the image of him standing up after fixing a pipe, meeting the grateful gaze of the homeowner. She could almost feel Tony's initial awkwardness, the silent tension as he prepared to leave.

"Is everything okay at work?" Rosella inquired. "Yes, everything's fine," Eilis quickly replied.

"You seem distracted. Just now." "Work is keeping me busy. That's all."

As Larry entered and pecked her on the cheek, he gestured towards his feet.

"My shoes are clean, but I've left them outside. I need to catch the news on the radio. I'll be in my room if anyone needs me."

"Who would be looking for you?"

"Many people. You'd be surprised."

As the day came to an end, Tony made his usual routine of showering and changing before seeking out his daughter, Rosella. Eilis often eavesdropped on their conversations, picking up bits of information that Tony shared with Rosella.

Meanwhile, Eilis added potatoes to the stew she had prepared the night before while Larry set the table. She tried to avoid Tony's presence, who was now in the living room watching TV. His jovial and thoughtful nature filled the house, contrasting with the complaints of her sisters-in-law about their husbands' lack of humor at home.

When Rosella mentioned to her grandmother how lovely her father was at home, her grandmother suggested that Lena and Clara could learn from Eilis to make their husbands more cheerful, hinting at Eilis's positive influence on those around her.

"She never says anything she doesn't mean," Rosella remarked.

Eilis stood with her back to the door, tending to the stew and washing dishes at the sink. She silently wished for this moment to last, for Tony to be engrossed in something on the television, delaying his arrival at the table. When he finally entered the room, she focused on drying plates, momentarily unsure of the usual dinner serving order. Should she serve Tony first, or perhaps Larry, the youngest, or Rosella? With a sense of resolve, she dished out the stew and carried two plates to Rosella and Larry. Without a word or a glance at Tony, she fetched the remaining plates. Meanwhile, Tony regaled Rosella and Larry with a tale of a dog attack while he was halfway inside a cupboard fixing a leaky pipe.

"The brute grabbed hold of my trousers and started tugging. And the owner, a Norwegian woman, had never had a man in her apartment before," Tony recounted.

Eilis listened, knowing he was oblivious to how his story resonated with her. Setting aside her own plate, she picked up Tony's and crossed the room. Just as she was about to place the plate on the table, she tilted it, causing stew to spill. She continued tilting until the food cascaded onto the floor near Tony. Startled, he looked up at her as she stood motionless, holding the empty plate.

Rosella hurried over, taking the plate from her mother, while Tony and Larry rearranged the table and chairs to clean the floor. Tony began picking up stew remnants from the ground.

"What happened to you?" Rosella inquired. "You just stood there."

Eilis kept her eyes on Tony, who had fetched a sponge and a bowl of water. She was waiting for him to look at her again.

"There's more stew in the pot," Larry said.

With the floor cleaned and the table back in place, and with a fresh helping of stew for Tony, they ate in silence. If Tony were to speak, Eilis was ready to interrupt him. She realized that Rosella and Larry must see that there was something happening between their parents. But it was Tony on whom Eilis was concentrating; he must be aware that she knew.