Terry Anderson, American Journalist and Former Hostage, Passes Away at 76

Terry Anderson, the globe-trotting Associated Press correspondent who was held captive for nearly seven years after being abducted in Lebanon in 1985, has passed away at the age of 76.

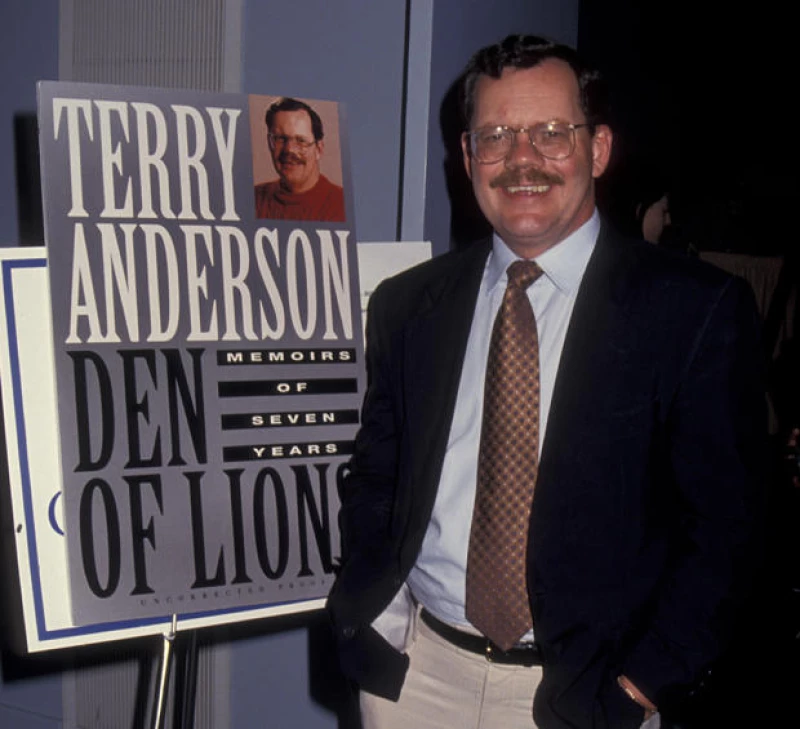

Anderson, known for his book "Den of Lions" where he detailed his harrowing experience as a hostage of Islamic militants, died at his home in Greenwood Lake, New York. His daughter, Sulome Anderson, confirmed that he passed away due to complications from recent heart surgery.

Reflecting on her father's legacy, Sulome Anderson shared, "He never liked to be called a hero, but that's what everyone persisted in calling him. I saw him a week ago and my partner asked him if he had anything on his bucket list, anything that he wanted to do. He said, 'I've lived so much and I've done so much. I'm content.'"

Life of Former Hostage Terry Anderson

Upon returning to the United States in 1991, Terry Anderson embarked on a varied journey, which included giving public speeches, teaching journalism, and managing different businesses such as a blues bar, Cajun restaurant, horse ranch, and gourmet restaurant.

Despite his successes, Anderson also faced challenges, including post-traumatic stress disorder, financial difficulties, and a bankruptcy filing in 2009. However, he continued to persevere.

In 2015, after retiring from the University of Florida, Anderson found solace on a small horse farm in rural northern Virginia, where he enjoyed the quiet and peaceful surroundings.

Reflecting on his life, Anderson once said, "I live in the country and it's reasonably good weather and quiet out here and a nice place, so I'm doing all right."

Remembering Terry Anderson

In a statement to CBS News, Anderson's daughter, Sulome Anderson, shared, "Though my father's life was marked by extreme suffering during his time as a hostage in captivity, he found a quiet, comfortable peace in recent years. I know he would choose to be remembered not by his very worst experience, but through his humanitarian work with various causes."

Back in 1985, Anderson found himself among the Westerners taken captive by Hezbollah, the Shiite Muslim group, in the midst of Lebanon's turmoil.

It was on a day off, March 16, 1985, when he had decided to enjoy a game of tennis with former AP photographer Don Mell. Little did he know that as he dropped off Mell at his residence, armed kidnappers would forcibly remove him from his vehicle.

He later revealed that he was likely singled out due to being one of the last Westerners remaining in Lebanon and his occupation as a journalist raised suspicions among the Hezbollah members.

"To them, individuals who venture into risky and challenging environments to seek answers are viewed as spies," he shared with The Review of Orange County in 2018.

What ensued was an agonizing period of almost seven years where he endured physical abuse, was shackled to walls, faced constant death threats, had guns pointed at him frequently, and was subjected to extended periods of isolation.

Hostage Recounts Time in Captivity

During his time in captivity, Anderson, the longest-held Western hostage abducted by Hezbollah, was known for his resilience and defiance. Despite the challenging conditions, he maintained a sense of humor, even joking with his captors about his escape plans.

According to accounts from Anderson and other hostages, he was a spirited captive, advocating for better treatment and engaging in intellectual debates with his captors. He also took on a mentorship role, teaching fellow hostages sign language and strategies for communication.

One particularly memorable moment was when Anderson tricked his kidnappers into believing he had already escaped, leading to a lighthearted exchange with one of them.

Anderson's resilience and wit during his captivity left a lasting impression on those who knew him, including Mell, who emphasized the unique bond they shared.

"Our connection went far beyond that single incident," Mell expressed.

Mell recognized Anderson for kickstarting his journalism career, advocating for the young photographer to secure a full-time position at the AP. Following Anderson's release, their bond grew stronger. They stood as each other's best man at their weddings and remained in constant communication.

Upon his return, Anderson was warmly welcomed at AP's headquarters in New York.

On Sunday, Louis D. Boccardi, the AP's president and CEO at the time, reminisced that Anderson's situation was always on the minds of his AP colleagues.

"If you keep the hatred you can't have the joy"

Anderson's wit often masked the PTSD he openly admitted to struggling with for years afterward.

Reflections on Healing from Trauma

"The AP got a couple of British experts in hostage decompression, clinical psychiatrists, to counsel my wife and myself and they were very useful," he said in 2018. "But one of the problems I had was I did not recognize sufficiently the damage that had been done.

"So, when people ask me, you know, 'Are you over it?' Well, I don't know. No, not really. It's there. I don't think about it much these days, it's not central to my life. But it's there," he said.

Anderson shared that his faith as a Christian played a significant role in helping him release the anger he carried. He also mentioned that a piece of advice from his wife later became instrumental in his healing journey: "If you keep the hatred you can't have the joy."

During his abduction, Anderson was preparing to get married, and his fiancee was six months pregnant with their daughter, Sulome.

Following his release, the couple tied the knot but eventually parted ways, maintaining an amicable relationship. However, Anderson and his daughter experienced a period of estrangement.

"I love my dad very much. My dad has always loved me. I just didn't know that because he wasn't able to show it to me," Sulome Anderson shared with the AP in 2017.

After the release of her well-received book, "The Hostage's Daughter," in 2017, where she recounted her journey to Lebanon to meet and forgive one of her father's captors, father and daughter reconciled.

"I believe she undertook some remarkable endeavors, embarked on a challenging personal journey, and ultimately produced a significant piece of journalism," Anderson reflected. "She has now surpassed my own achievements as a journalist."

Terry Alan Anderson came into the world on October 27, 1947. His early years were spent in the quaint Lake Erie town of Vermilion, Ohio, where his father served as a police officer.

Instead of accepting a scholarship to the University of Michigan after high school, he opted to enlist in the Marines. During his time in the military, he reached the rank of staff sergeant and experienced combat in the Vietnam War.

"It was actually the most captivating role I've ever held," he shared with The Review. "It was intense. War was ongoing — it was extremely perilous in Beirut. A brutal civil war, and I managed to last about three years before I was taken captive."

Anderson was married and divorced three times. Alongside his daughter Sulome, he is also survived by another daughter, Gabrielle Anderson, from his first marriage; a sister, Judy Anderson; and a brother, Jack Anderson.