During this week, a group of women who worked in factories during World War II and served as the inspiration for "Rosie the Riveter" will finally receive the long-awaited Congressional Gold Medal.

Among these women are individuals in their 80s, with some even reaching the age of 100. Out of the millions of women who contributed exceptional service during the war, only a handful remain to witness the acknowledgment of their efforts with one of the country's most prestigious honors.

One of the remarkable women being recognized is Susan King, who at 99 years old, continues to operate a rivet gun just like she did while assisting in the construction of warplanes at Baltimore's Eastern Aircraft Factory. King embarked on her journey at the factory when she was 18 years old, becoming one of the 20 million workers who obtained credentials as defense workers to fill the roles left vacant by men drafted into the war.

"I never saw myself as just a factory worker," reflected King. "I was doing this to avoid having to work as a maid."

The Forgotten Women of World War II

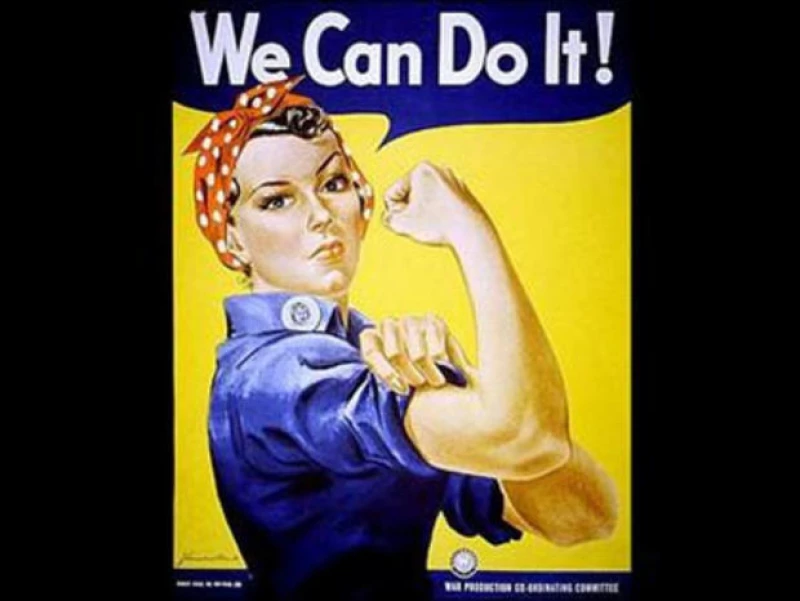

During World War II, a group of hardworking women took on jobs traditionally held by men to support the war effort. These women, known as "Rosie the Riveters," worked tirelessly in factories and shipyards, contributing significantly to the war industry.

Despite their crucial role, the Rosies did not receive the recognition they deserved after the war ended. While veterans were honored with parades and medals, many Rosies lost their jobs and were forgotten. It took decades for their service and sacrifice to be appreciated.

Gregory Cooke, a historian and son of a Rosie, believes that the lack of appreciation stems from gender bias. "I don't think White women have ever gotten their just due as Rosies for the work they did on World War II, and then we go into Black women," Cooke said.

To shed light on the forgotten Rosies, Cooke produced and directed a documentary called "Invisible Warriors," which highlights the stories of these remarkable women. One of the few Black Rosies who understood her significance was Mrs. King, according to Cooke.

Today, the memory of the Rosies is being preserved at various historical sites, including the Glenn L. Martin Aviation Museum in Maryland and the Rosie the Riveter National Historic Park in Richmond, California. These sites serve as a tribute to the women who played a vital role in the war effort.

During the war, Sousa and her family joined forces in the effort. Her two sisters, Phyllis and Marge, took on welding duties while her mother Mildred worked as a spray painter. "It gave me a backbone," Sousa reflected. "There was a lot of men who still were holding back on this. They didn't want women out of the kitchen."

Phyllis Gould, Sousa's sister, played a prominent role in advocating for recognition of the Rosies. In 2014, she, along with other Rosies, was invited to the White House after sending a letter to then-Vice President Joe Biden urging the establishment of a National Rosie the Riveter Day. Gould was instrumental in designing the Congressional Gold Medal that will be issued. However, Gould passed away in 2021 at the age of 99 and will not be present in Washington, D.C. this week.

On Wednesday, about 30 Riveters will be honored, with King being among them.

"I guess I've lived long enough to be Black and important in America," expressed King. "And that's the way I put it. If I were not near a hundred years old, if I were not Black, if I had not done these, I would never have gone to Washington."