In a significant move to protect public health, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has announced a comprehensive ban on asbestos, a known carcinogen still present in some chlorine bleach, brake pads, and other products, leading to tens of thousands of deaths annually.

This final rule signifies a significant expansion of EPA regulations following a 2016 law revision that aimed to govern numerous toxic chemicals present in everyday items, ranging from household cleaners to clothing and furniture.

The new regulation will specifically target chrysotile asbestos, the sole remaining asbestos use in the U.S., commonly found in products like brake linings, gaskets, and utilized in the production of chlorine bleach and sodium hydroxide (caustic soda).

EPA Administrator Michael Regan emphasized the importance of this final rule in safeguarding public health, stating, "With today's ban, EPA is finally slamming the door on a chemical so dangerous that it has been banned in over 50 countries. This historic ban is more than 30 years in the making, and it's thanks to amendments that Congress made in 2016 to fix the Toxic Substances Control Act, the primary U.S. law overseeing chemical usage."

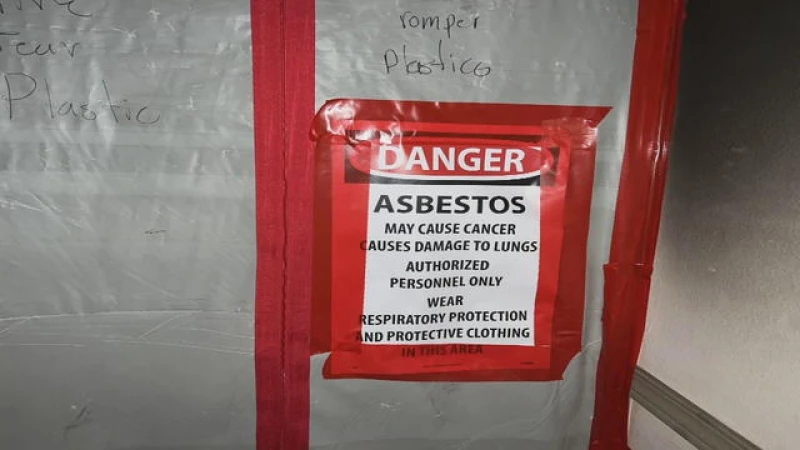

Exposure to asbestos is known to cause lung cancer, mesothelioma and other cancers, and it is linked to more than 40,000 deaths in the U.S. each year. Ending the ongoing uses of asbestos advances the goals of President Joe Biden's Cancer Moonshot, a whole-of-government initiative to end cancer in the U.S., Regan said.

"The science is clear: Asbestos is a known carcinogen that has severe impacts on public health. This action is just the beginning as we work to protect all American families, workers and communities from toxic chemicals,'' Regan said.

The 2016 law authorized new rules for tens of thousands of toxic chemicals found in everyday products, including substances such as asbestos and trichloroethylene that for decades have been known to cause cancer yet were largely unregulated under federal law. Known as the Frank Lautenberg Chemical Safety Act, the law was intended to clear up a hodgepodge of state rules governing chemicals and update the Toxic Substances Control Act, a 1976 law that had remained unchanged for 40 years.

The EPA banned asbestos in 1989, but the rule was largely overturned by a 1991 court decision that weakened the EPA's authority under TSCA to address risks to human health from asbestos or other existing chemicals. The 2016 law required the EPA to evaluate chemicals and put in place protections against unreasonable risks.

Asbestos, which was once common in home insulation and other products, is banned in more than 50 countries, and its use in the U.S. has been declining for decades.

Dr. Arthur Frank, an environmental and occupational health expert at Drexel University who's been researching asbestos for decades, stated in an interview with CBS Philadelphia last year that many buildings constructed before 1970 "are very likely to have asbestos."

Frank elaborated that when asbestos is disturbed, particles can become airborne and, if breathed in, may lead to lung damage.

"There's no known safe level of exposure to asbestos in relation to cancer development," Frank emphasized.

The sole type of asbestos currently imported, processed, or distributed for use in the U.S. is chrysotile asbestos, primarily brought in from Brazil and Russia. It is utilized by the chlor-alkali industry, which manufactures bleach, caustic soda, and other items.

Most consumer goods that previously contained chrysotile asbestos have been discontinued.

Although chlorine is a widely used disinfectant in water treatment, there are only 10 chlor-alkali plants in the U.S. that still utilize asbestos diaphragms to produce chlorine and sodium hydroxide. These plants are primarily situated in Louisiana and Texas.

The utilization of asbestos diaphragms has been decreasing and now represents approximately one-third of the chlor-alkali production in the U.S., as reported by the EPA.

In a significant move, the EPA has announced a new rule that will prohibit the import of asbestos for chlor-alkali use upon publication, with a broader ban on most other uses set to come into effect in two years.

Specifically, the use of asbestos in oilfield brake blocks, aftermarket automotive brakes and linings, and certain gaskets will be banned in six months. Additionally, a ban on sheet gaskets containing asbestos will be implemented in two years, except for those used in the production of titanium dioxide and for nuclear material processing, which will be phased out in five years.

Interestingly, the EPA has granted an exception for asbestos-containing sheet gaskets at the U.S. Department of Energy's Savannah River Site in South Carolina until 2037 to facilitate the safe disposal of nuclear materials as per schedule.

Scott Faber, the senior vice president of the Environmental Working Group, a prominent advocacy organization that advocated for the asbestos ban, expressed his appreciation for the EPA's decision.

"For too long, companies have been allowed to manufacture, use, and release hazardous substances like asbestos and PFAS without considering the impact on our health," Faber remarked. "Thanks to the proactive measures taken by the Biden administration's EPA, this era of negligence is finally coming to an end."