Panama City

A team of international scientists working on a research vessel off the coast of Panama is looking for something you might think would be hard to find.

"We are exploring the unexplored," Alvise Vianello, an associate chemistry professor at Aalborg University in Denmark, told CBS News. "…It's like, you know, finding the needle in the haystack."

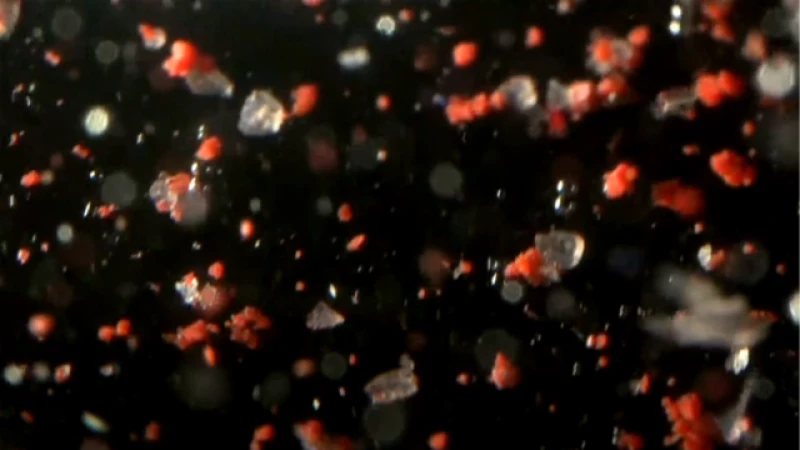

In this case, the needle is microplastic, and the ocean is drowning in it.

An estimated 33 billion pounds of the world's plastic trash enters the oceans every year, according to the nonprofit conservation group Oceana, eventually breaking down into tiny fragments. A 2020 study found 1.9 million microplastic pieces in an area of about 11 square feet in the Mediterranean Sea.

"Microplastics are small plastic fragments that are smaller than 5 millimeters," Vianello said.

The researchers are trying to fill in a missing piece of the microplastic puzzle.

"I want to know what is happening to them when they enter into the ocean. It's important to understand how they are moving from the surface to the seafloor," said researcher Laura Simon, also with Aalborg University.

According to a recent study, approximately 70% of marine debris sinks to the seafloor, but its impact remains largely unknown. The study, conducted by the 5 Gyres Institute and published in March, estimates that there are now 170 trillion pieces of plastic in the ocean, which amounts to more than 21,000 pieces for every person on Earth.

Researchers have found that certain types of fish, such as tuna, swordfish, and sardines, may be ingesting these microplastics, which raises concerns about the potential effects on human health.

By collecting and analyzing data on microplastics, scientists hope to gain a better understanding of how these pollutants are impacting various aspects, including the ocean's ability to regulate the Earth's temperature.

The research is being conducted aboard a ship owned by the Schmidt Ocean Institute, a nonprofit organization funded by former Google CEO Eric Schmidt and his wife Wendy. The Schmidts allow scientists to use the ship free of charge, with the condition that they share their data with researchers worldwide.

"The knowledge gained from studying plastic pollution is starting to change people's perspectives," said Vianello, one of the researchers involved in the study.

This shift may be attributed to the realization that many items we consider disposable actually persist in the environment.